A big abrazo to everyone who participated in our discussion thread last Thursday on Title 42. It was a big success!

Thank you once again to our guests: Gaby Del Valle from BORDER/LINES, Blake Gentry of the Alianza Indigena Sin Fronteras, Erika Pinheiro of Al Otro Lado, Jesse Franzblau from the National Immigrant Justice Center, and Noah Schramm from the Border Action Team of the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project. We appreciate ya!

I learned a lot from the discussion about what to expect when Title 42 is lifted in May (if it’s lifted). And also about who benefits if Title 42 remains (some interesting answers from our invited experts!). The Border Chronicle loves bringing knowledgeable people with diverse perspectives together to discuss the complex issues that border communities deal with every day. If you’re signed up as a free subscriber and find our work valuable, please consider becoming a paid subscriber so we can continue our work and become sustainable in 2022.

I’m mixing it up with today’s post. Fellow journalist Ana Adlerstein hit the road with me on Saturday and we traveled to Yuma, Arizona. In this dispatch we included text and photos, and Ana included a five-minute audio piece she edited. Hope you enjoy it!

Reporter’s Notebook: A Man and His Rake vs. Anti-immigrant Hate in Yuma, Arizona

The Border Chronicle visits with Fernando “Fernie” Quiroz, director of the AZ-CA Humanitarian Coalition that provides aid to asylum seekers in Yuma

In the most parched corner of the Sonoran Desert on the Arizona-California border sits Yuma, Arizona. It’s a place of extremes. A trickle of water that was once the mighty Colorado River runs through this desert, and there is row after row of waving wheat and green lettuce fields—part of a multimillion-dollar produce industry—which seems almost impossible, like a mirage.

Once, the Colorado River flowed through Yuma on its way to the Sea of Cortez in Mexico. Now it’s a dried-up riverbed. What’s left of the Colorado has been reduced to a narrow concrete irrigation canal.

Fernando “Fernie” Quiroz, 49, remembers when the Colorado River still flowed to Mexico. In San Luis Río Colorado, Sonora, just south of Yuma, where his family is originally from, there was a bridge that the town’s residents used to cross the river into Baja California. “The river has been dry now,” he says, “for at least 30 years.”

The youngest of 13 siblings, Quiroz worked with his family picking crops in Yuma and in neighboring California. When he was 18, he stopped working in the fields, went to university, and earned a degree in molecular cellular biology. “I am a son of immigrants,” he says. “My mother came to this country for one reason, to give me a better life. And I had the opportunity to get that life. And why should I turn my back?”

Quiroz is referring to the men, women, and children who walk from Mexico through the dried Colorado River bed to request asylum from the Border Patrol agents waiting at gaps in the 30-foot border wall that divides Algodones, Mexico, from his hometown.

Quiroz is director of the AZ-CA Humanitarian Coalition, a volunteer group in Yuma that provides aid to asylum seekers who began arriving after the ports of entry closed under the Trump administration due to Title 42 and other measures. The coalition provides snacks and water. “We pushed for bathrooms to be put out there and water stations,” he says. “And Border Patrol has agreed to those things.”

But one of the biggest sticking points has been trash and recycling bins. Yuma Sector Border Patrol has made it a policy that each asylum seeker can bring only what they can fit into a small plastic Department of Homeland Security bag.

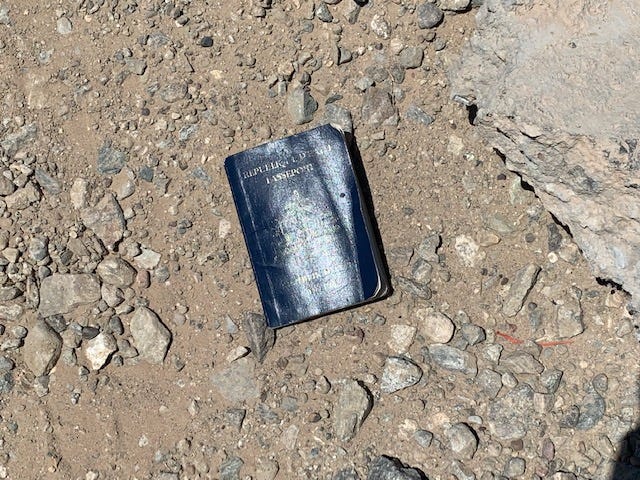

This means piles of shoes, makeup bags, toys, good-luck charms, prayer cards, and other belongings are left behind on the dirt levee road next to the border wall. In the media and among right-wing politicians and anti-immigrant militia groups, these belongings are often portrayed as “trash left by illegal immigrants,” says Quiroz.

Countering this message has become Quiroz’s mission. Nearly every day he shows up at the border wall with his rake and makes tidy piles of the items left behind, then bags it up and hauls it away. His 16-year-old daughter and six to eight other volunteers also do cleanup.

“It’s not that they’re leaving a mess,” he says. “When Border Patrol shows up, they tell them to drop everything and get in line.”

There used to be piles of clothes, shoes, and other personal items strewn all over the ground. Quiroz and the coalition worked with the county to have dumpsters left at the site to try and improve the conditions.

Quiroz says a lot of people, including some local officials, oppose what the coalition is doing. On weekends, a white-supremacist militia called the Arizona Patriots often comes out and patrols the same area, destroying the food that the coalition leaves out for asylum seekers. “They’re dressed in camo, they have guns, and they harass and tell the people as they’re coming across that they’re not welcome,” Quiroz says.

As he sifts through the abandoned items, Quiroz often thinks of the people who left them behind. He finds a pair of newly handmade shorts made of burlap, then picks up a worn wallet from the dirt that contains only a saint card and a typewritten prayer in Spanish for “protection from my enemies.”

Quiroz says he does the clean up because he wants people to see the asylum seekers as fellow humans in need, not to focus on the piles of items that are left behind, which then become the dominant narrative in the media. “That’s not the visual I want people to see,” he says. “The anti-immigrant message that takes away the human aspect of these people.”

Quiroz says he started doing the trash runs in 2021. Personal belongings were strewn everywhere, and it was a mess, he says. “My brother and I, we spent three days in a row from sunrise to sundown with a trailer to haul everything to the dump,” he says. “And there were no trash bins.”

His goal now, he says, is to save all the gently used clothing items and shoes that they find, and get them cleaned and washed so that they can be donated to migrant shelters. Quiroz and I examine the piles of things left next to the dumpsters, and there are Nike tennis shoes, women’s dress shoes, baby clothes, even a National Geographic expeditions bag.

“I’m getting calls from Casa Alitas and other shelters and they’re asking me, Why are people showing up with no clothes, no backpacks?” he says. “And now you imagine that hardship that occurs for them. Because they had that one extra set of clothes, and they had to throw it away.”

Quiroz says he still believes in the promise and hope of the American Dream. And he wants the people who arrive to feel that hope too, even if they have a long and difficult road ahead of them in winning their asylum cases. “The Statue of Liberty still stands there, giving light to this amazing country,” he says. “I am the son of immigrants. This is still a country of immigrants. But some of us choose to forget.”

To volunteer or learn more about the AZ-CA Humanitarian Coalition contact Natalie Hernandez, volunteer coordinator at (928) 581-1912.