The Borderlands’ Lost Third Country

Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue’s new novel, Now I Surrender, is an epic about the U.S. and Mexico’s joint erasure of Apachería.

One of North America’s Last Pristine Prairies in the San Rafael Valley Will Be Scarred Forever as the Border Wall Advances in Southern Arizona.

The Trump administration is rapidly advancing border wall construction across the southern border, spending billions while ignoring federal protections like the Endangered Species Act. The Border Chronicle is featuring perspectives from border residents who have worked closely on border wall issues. Myles Traphagen, based in Tucson, is the Borderlands Program Coordinator for the nonprofit Wildlands Network. — Melissa

In mid-August, during what should have been the peak of the summer monsoon season, we were experiencing what southern Arizonans despairingly call a “non-soon.” The normally lush green grasslands of the San Rafael Valley were brown, crisp, and dry. Red dirt roads were swept up into the sky by dust devils dancing across the valley floor, their funnels twisting high into the air.

Wells were drying up on ranches, and 18-wheeler trucks were being loaded with cattle because they could no longer be sustained after years of drought. Scores of dead alligator juniper trees lined the foothills of the valley.

Amid these ominous signs of drought, I spotted something much more sinister: wooden survey stakes lining the Roosevelt Reservation, the 60-foot-wide, 632-mile-long strip of land along the U.S.-Mexico border set aside by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907 for federal access. This easement, established by the “father of American conservation,” has ironically enabled the rapid expansion of border walls.

When I saw the stakes, they elicited a feeling similar to witnessing a loved one at the end of life—a sense of stinging inevitability. The words “DO NOT DISTURB” were written on the stakes.

The Fisher Sand and Gravel company had arrived to disfigure one of the finest grasslands in the Southwest. Tommy Fisher, a Trump ally and CEO of a company with a checkered past, was awarded a $309 million contract to build 27 miles of 30-foot-tall steel border wall for the Tucson Sonoita Project. This unnecessary border wall will require millions of gallons of scarce groundwater and create a permanent scar across a millennia-old valley that is the heartland of Arizona and Sonoran heritage. As of mid-December, nearly a mile of primary border wall has been built—30 feet tall, with an eight-foot concrete footer. Soon, CBP plans to add a secondary wall, resembling a maximum-security prison with a surveillance zone in between, complete with cameras and high-intensity lighting. The once-beautiful wildlife corridor will now be solely for surveillance and armed federal agents.

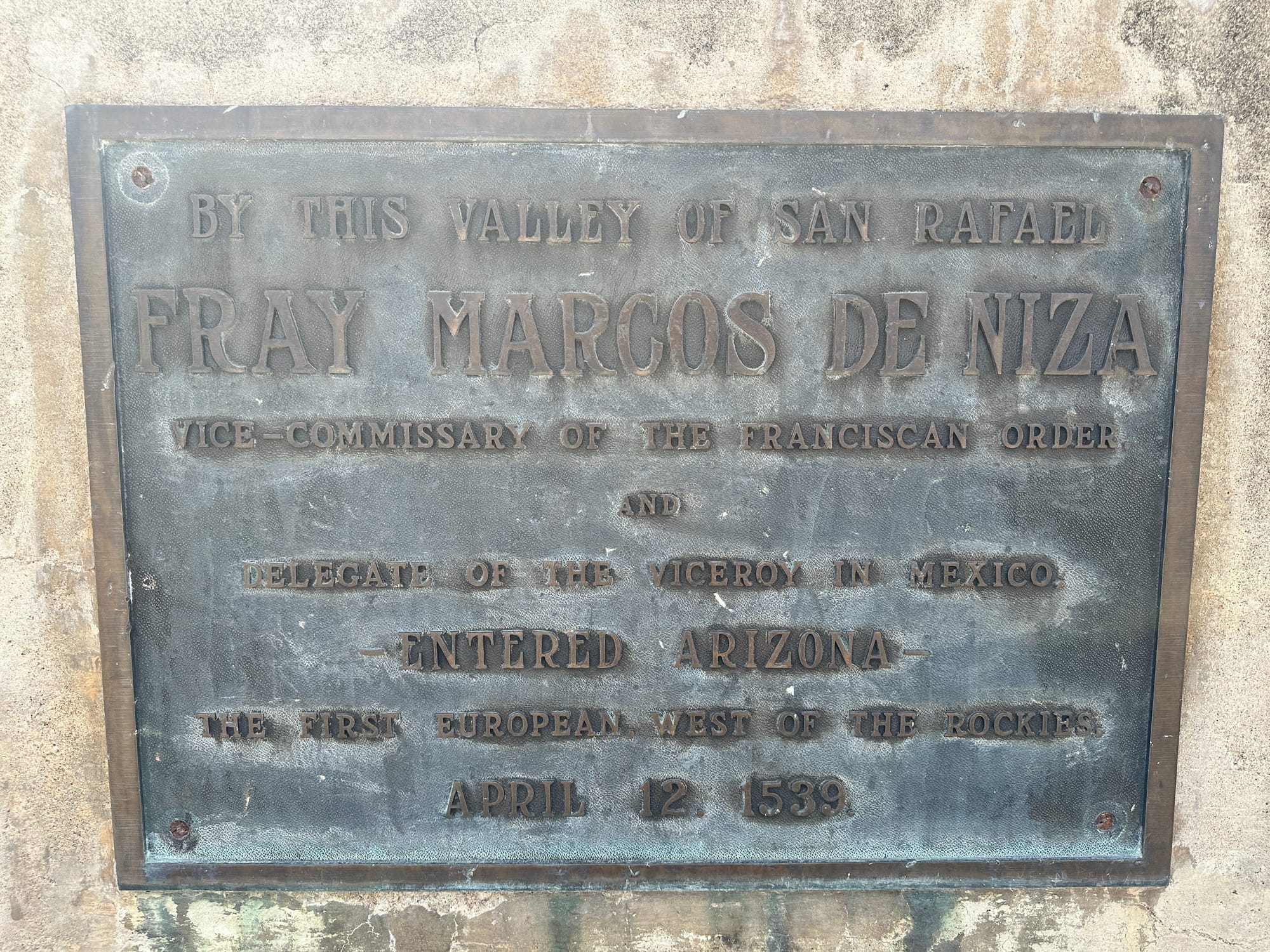

Although most Americans have never heard of the San Rafael Valley, it looms large in our cultural and natural history. In 1539, Fray Marcos de Niza became the first European to enter western North America near what is now Lochiel. A year later, the Coronado expedition followed, marking the beginning of European settlement of the West. Ironically, nearly 500 years later, a wall is being built to keep foreigners out. Despite its remoteness, many Americans have seen this valley without realizing it. In 1955, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! was filmed here. Why would filmmakers choose the Arizona borderlands instead of the heartland itself? Producer Arthur Hornblow explained, “Today’s Oklahoma does not look like it did in 1907.” But the San Rafael Valley still held the sweeping, belly-high-to-a-horse blue grama grasslands that once defined Indian Territory—before sod-busting and oil booms forever transformed Oklahoma into an agro-industrial landscape.

Here in the borderlands of the San Rafael Valley, giant sacaton grass still brushes the bellies of cattle and horses tended by cowboys and vaqueros who, like generations before them, call this landscape home. Wildlife thrives—porcupines, pronghorn, black bears, ocelots, and the Coues white-tailed deer, the smallest subspecies of deer and a borderlands specialty prized by hunters across North America. The valley is also one of the most important wildlife corridors between the U.S. and Mexico. Recent trail camera photos confirm that jaguars still roam the surrounding Huachuca, Santa Rita, and Patagonia mountains, which cradle the San Rafael Valley and give birth to two rivers, the San Pedro and the Santa Cruz. Human presence remains scarce here; Mexico’s Highway 2 lies more than 20 miles south and Sonoita even farther north. This exposed valley, consisting mostly of privately owned land, is a less-than-ideal migration corridor for people. CBP’s network of Integrated Fixed Towers increases the probability of detection.

The ongoing five-year Border Wildlife Study by Sky Island Alliance has documented on camera more than 160 wildlife species. Yet fewer than 0.5 percent of detections were humans—most were hunters, birders, and people recreating legally. This border wall—declared under one of Trump’s 10 “national emergencies”—is unnecessary and unjustified. Sky Island’s data corroborate CBP data showing that unauthorized border crossings are at a historic low. The invasion is coming from Washington.

Building this wall will waste millions of gallons of groundwater, permanently altering the lives of every being that depends on this land, especially downstream communities in Sonora. Hard-rock mines surrounding the valley drain scarce water, but at least they produce commodities that provide tangible benefits. What does a border wall give us? It does not wire homes or power cars—it is nothing but an eyesore and a killing machine that inflicts suffering on people and animals.

This eyesore is front and center on the western slope of Coronado Peak at Coronado National Memorial, a site commemorating the expedition of Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, who passed through the San Rafael Valley in 1540 in search of gold in the Seven Cities of Cíbola. In November contractors for Fisher Sand and Gravel began blasting Coronado Peak with dynamite to obtain gravel for the border wall and gouge a road across the mountain. They are literally blowing up part of a national park. How can this be possible? Aren’t these protected lands?

Sort of. Congress inserted a provision into the Real ID Act of 2005 granting the secretary of Homeland Security—a nonelected, politically appointed official—the authority to waive virtually all laws for border wall construction. These include the Endangered Species Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, the Clean Water Act, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, and the National Scenic Trails Act. The waiver directly affects the Coronado National Memorial. At Border Monument 102, located at the southern foot of the Huachuca Mountains within the memorial, the Arizona National Scenic Trail reaches its southern terminus. But the trail is now truncated, and thousands of hikers who once celebrated their 800-mile overland journey from the Utah border to the U.S.-Mexico border are now unable to reach their final step. Monument 102 was recently wrapped in concertina (razor) wire, and public access is restricted. The razor wire poses a lethal threat to wildlife. We are ceding public lands in the name of border insecurity.

On December 2 a small group of us witnessed a horrific dynamite blast inside the national memorial. This is unacceptable. Our national parks and monuments are sacred places, designated for their exceptional qualities that should be protected for future generations. Yet a single Department of Homeland Security official has exercised unchecked control over public lands, bypassing Congress and the courts. Nothing feels sacred anymore.

In the western San Rafael Valley near Lochiel, giant cottonwoods shade the glades of the Santa Cruz River before it flows south into Sonora, Mexico. This quintessential binational river then returns to Arizona at Kino Springs, passing Tubac and Tucson before joining the Gila River on its way to the Colorado River. Yet, Lady Liberty’s arms will no longer provide a welcoming embrace when the river returns to the Land of the Free because border wall construction is underway to close the quarter-mile gap where the Santa Cruz crosses the border. This small but crucial gap has provided safe passage for wildlife and people for the last 10,000 years. Blocking these corridors will alter the evolutionary history of the continent.

There are things you can replace and others you cannot. The intrinsic value of wild, open landscapes cannot be measured—it can only be felt. I urge you to visit the Fray Marcos de Niza Monument at Lochiel, then drive to Montezuma Pass at Coronado National Memorial. Experience this peaceful prairie while you still can. It may be your last chance to see the heartland of North America as Coronado saw it.

Support independent journalism from the U.S.-Mexico border. Become a paid subscriber today for just $6 a month or $60 a year.

Independent news, culture and context from the U.S.-Mexico border.